Welcome to “Brutalist Buildings,” a Facebook page dedicated to, you guessed it right, brutalist-style architecture worldwide! From the towering giants of the concrete jungle to hidden gems nestled among urban landscapes, this page is a treasure trove for architecture enthusiasts and anyone who appreciates the unique charm of the brutalist design.

If you love significant concrete buildings or find their shapes fascinating, you’re in for a treat! We’ve gathered the best pics of brutalist architectural marvels. So, take a moment to relax, sit back, and be amazed by the captivating realm of “brutalist Buildings.”

To delve deeper into the world of brutalist style, we contacted experts in the field. Alex Anderson, Ph.D., an Associate Professor in Architecture at the University of Washington, and Dr. Angela Person, an Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma, provided valuable insights. Please scroll down to learn more about this fascinating architectural movement of brutalist architecture and gain a deeper appreciation for its impressive structures. (H/T)

01. Private House (1965) In Zürich, Switzerland

Architect: Hans Demarmels

02. Foundation For Medical Researches – “La Tulipe” (1976) In Genève / Geneva, Switzerland

Architect: Jack Vicajee Bertoli

Photo: Magda Ghali

03. Building Plurioso (1972) In Rome, Italy

Architect: Saverio Busiri Vici

Photo: Il Conte Photography

Before we delve into the intricacies of brutalism, let’s take a moment to understand what this style is all about. We’ve received a brief and insightful lecture from Alex Anderson, Ph.D. According to the professor, “brutalism” helps explain its characteristics. “‘Béton brut,’ which means ‘raw concrete,’ is a French term used to describe exposed concrete. This was often used to describe the material when its use in architecture became more common in the mid-20th century. So, the root of ‘brutalism’ to describe architecture is ‘raw,’ that is: unembellished, unornamented, unhidden. To learn more about architecture overview, check out this article.

A key characteristic of brutalism is that it exposes the basic materials and systems used in buildings. While concrete is a common and essential material for brutalism, it isn’t the only material. For example, an early and well-known example by the British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, the Hunstanton School (1954), used relatively little concrete.

04. Estate Parkitka (Project: 1986-89) In Częstochowa, Poland

Architect: Marian Kruszyński

05. Private House (1965) In Stabio, Switzerland

Architect: Mario Botta

Photo: Arnout Fonck

06. Armenian Writers Association’s Summer Residence, The Canteen (1969) In Sevan Peninsula, Armenia

Architect: Gevorg Kochar

Instead, it was built with an exposed steel frame with brick infill. The electrical conduit, water lines, drainage, and other building systems were left visible inside the building. The Smithsons explained that “this was an honest way of making architecture more ethical and economical than hiding everything away in hollow walls. We can understand ‘brutalism’ as a simple, frank, and unembellished architectural style. Of course, as with any style, variations developed almost immediately. Gradually, concrete became a dominant material.

One of its distinguishing characteristics is that it starts as a liquid molded in formwork. This formwork leaves an impression on the finished material, revealing the construction processes. Concrete shows the grain of the plywood forms, for example, and the regularly spaced holes left behind by the wire ties that hold two sides of the forms together (form-tie holes). The sculptural qualities of concrete allowed architects to use the material in a great variety of ways to make expressive, but still unornamented and ‘raw’ buildings (Boston City Hall (1968) is a good example).”

07. Heidi Weber Museum (1967) In Zürich, Switzerland

LateCorbusier With Metal And Glass And With Some Brutalist Details

Architect: Le Corbusier

08. Lamela Residential Building (1976) In Zenica, Bosnia And Herzegovina

Architect: Slobodan Jovandić

09. Zvartnots International Airport (1970s), Under Demolition Threat (Expanded With New Parts In 1998 And 2004) In Yerevan, Armenia

Architects: S. Bagdasaryan, A. Tarkhanyan, S. Khachikyan, Zh. Shekhlyan, L. Cherkezyan – later involved А. Tigranyan and А. Meschyan

Photo: Rob Schoefield

According to Anderson, people’s fascination with brutalism is the name of the style. “In English, ‘brutal’ is much different than the French word ‘brut.’ A sense of nastiness is associated with the English term not present in French. Any architectural style called ‘brutal’ or ‘brutalist’ will naturally elicit opinions! Thinking of architecture this way is fascinating because we usually consider it positive; it’s traditionally about beauty.

Brutalism draws attention to a different side of architecture, revealing construction techniques and systems we might never have noticed before because, in the past, they were considered ugly and were hidden away. On the positive side, many people have come to appreciate and like these more raw aspects of architecture and the exposure of its anatomy (this is a key to understanding the appeal of the Pompidou Center in Paris, for example).

On the negative side, this focus on the raw aspects of architecture has often drawn architects’ attention away from those parts of the architecture that have traditionally appealed to people, such as ornament and comfortable finishing materials. Exposed steel and concrete are austere, cold, and unfriendly; not everyone likes them. As a historian of architecture, I believe that brutalism offers fascinating insights into the purposes and motivations of architecture. Is architecture meant to be beautiful or honest? Is architecture more like traditional art (which is typically intended to be beautiful) or modern art (which is often meant to be unsettling)?”

10. Musmeci Bridge, Aka Bridge Over The Basento River (Designed In 1967, Started In 1971, Completed In 1976) In Potenza, Italy

Architect: Sergio Musmeci

11. Flamatt 1 (1958) House In Wünnewil-Flamatt (Near Bern), Switzerland

Architects: Atelier 5 (Erwin Fritz, Samuel Gerber, Rolf Hesterberg, Hans Hostettler, and Alfredo Pini – later joined: Niklaus Morgenthaler)

12. Faculty of Computer Science and Cybernetics at University Taras Shevchenko (1969) In Kyiv, Ukraine

Dr. Angela Person shed light on why people respond differently to brutalist architecture. “First, people with architecture and design training tend to be more sympathetic to these buildings. They often see brutalist Buildings not only in their foreboding scale but also in their unique compositional elements, the raw honesty of their materials, and the technical ingenuity required to design and construct them. But, to be fair, these same Brutalism lovers are not often the same people who have to live and work inside these buildings.

Talk to people who spend all day, every day, in brutalist office buildings, for example. You’ll often hear about issues with getting natural light into the interiors of the buildings, problems maintaining and repairing them, and difficulties adapting them to conform to new ways of working. Then, there are the everyday people who encounter these buildings on the street—people who aren’t designers and don’t work in the buildings but might still see them daily on their commutes home.

For these folks, it’s understandable that brutalist Buildings don’t make sense. Stylistically, they’re often very different from their surroundings, which can be jarring. When you’re walking down the street, they might feel menacing and unapproachable.”

13. Hotel Claridge (1969), Abandoned In Alarcón, Spain

14. Crafton Hills College (1972) In Yucaipa, California, U.S.

Architect: E. Stewart Williams

Photo: Darren Bradley

15. Tribute To Kevin Roche, Knights Of Columbus Building (1969) In New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.

Architectural firm: Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates

Photo: Seth Tisue

Brutalist buildings stand out in the places they are built and often spark solid reactions and emotions in people. Anderson shared that many brutalist buildings are bold and do not blend into their surroundings. “This can make them jarring,” the professor added. “As usual, there are two sides to this. In many cases, this makes them monumental. Monuments, by their nature, stand out. We are supposed to notice them.

Boston City Hall and the Pompidou Center are significant public buildings. They both stand out boldly from their surroundings and are closely tied to the era in which they were built. They are modern buildings. Many other city halls and museums use ancient styles of architecture—typically Greek or Roman—to make them stand out. Brutalist public buildings express more than material and construction processes; they announce themselves as buildings of and for the 20th century.

They are more about the present and future than the past. A great many brutalist Buildings, however, are not grand public buildings. They are schools, offices, research labs, fire stations, and libraries. When these more mundane buildings fail to blend into their surroundings and stand out like monuments, they can disrupt the fabric of their communities. Often people come to resent their intrusiveness.”

16. National Archives (Started In 1976, Completed In 1983) In Bratislava, Slovakia

Architect: Vladimír Dedeček

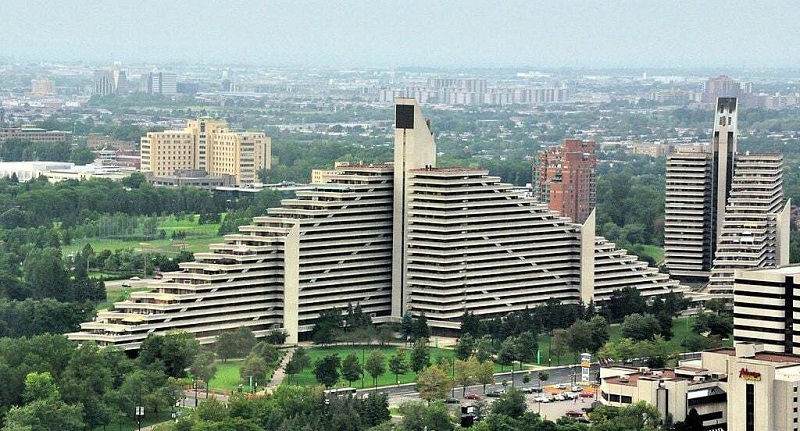

17. Residential House, Aka Olympic Pyramid (1976) In Montreal, Canada

Architects: Roger D’Astous and Luc Durand

18. Lila Acheson Wallace World Of Birds At The Bronx Zoo (1972) In New York, NY, U.S.

Architect: Morris Ketchum

We also asked the person what she thinks of how brutalist Buildings fit with the places around them. According to her, most brutalist architecture tends to contrast with its natural and urban surroundings. However, aesthetically speaking, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. “One excellent example is Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (completed in 1963) on the Harvard University campus.

When it opened, architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that its ‘assured, nonconformist rejection of the university’s carefully nurtured Colonial charm, both real and synthetic, is the source of most of the criticism.’ She continued by highlighting the Center’s obvious stylistic contrast with its more traditional, Neo-Georgian surroundings, writing that it ‘could not have been put down in a less sympathetic setting if it had been dropped from the moon.’

Today, more than 50 years after Huxtable wrote that it ‘manages to make everything around it look stolid and stale,’ I tend to see the building as complementary to its surroundings. Yes, it’s still very different from its neighboring buildings, but with mature landscaping and other relatively new buildings like Renzo Piano Building Workshop’s Harvard Art Museum renovation nearby, it feels less like a sore thumb and more like it’s ‘part of the team.'”

Whether brutalist architecture fits well or stands out in its surroundings depends on the culture and environment. The person added that we should also remember that the connection between each building and its environment can change over time.

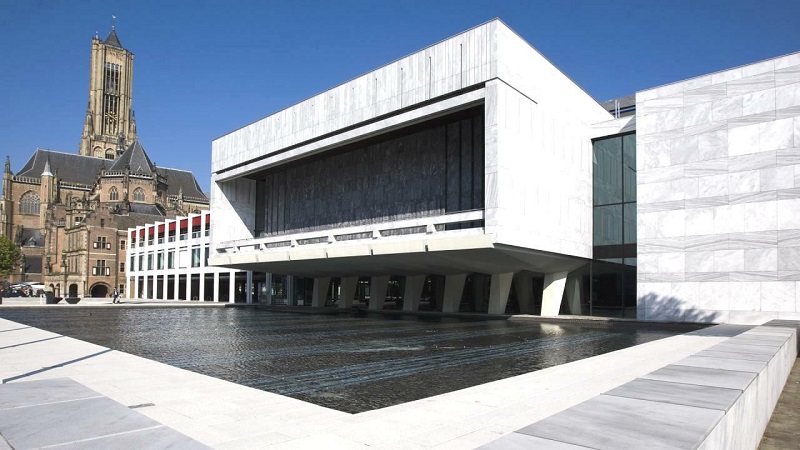

19. City Hall (1968) In Arnhem, Netherlands

Architect: Johannes Jacobus Konijnenburg

20. ENAIP Vocational Training Centre, Former Elementary School (1962) In Busto Arsizio (Near Milano / Milan), Italy

Architect: Enrico Castiglioni

Photo: Stefano Perego

21. Chapel Of The Cemetery Campos De Paz (1973) In Medellín, Colombia

Architect: Laureano Forero Ochoa

Photo: Dairo Correa

Brutalist architecture is known for its solid concrete buildings and striking shapes, which have fascinated and sparked criticism. However, some misconceptions and myths have arisen, clouding the natural beauty of this captivating style. The person helped us uncover and clarify some of these misunderstandings about brutalism. “One of my favorite misconceptions about brutalist architecture hits close to home. A prominent brutalist building on the University of Oklahoma campus, where I teach, is known as the Physical Science Center (completed in 1971).

When you go on a campus tour, the tour guides will tell you that it was ‘built to be riot proof’ during civil unrest on campuses during the American War in Vietnam. Through archival research, I found that the design of this building had nothing to do with riot-proofing the facility and everything to do with the architects’ desire to design and build one of the first poured concrete structures in the area. It was the style of the time, after all.

22. Gothard Observatory (1968) In Szombathely, Hungary

Architect: Elemér Zalotay

Photo: János Bődey / Index

23. Bank Of Israel (1974) In Jerusalem, Israel

Architects: Arieh and Eldar Sharon

Photo: Ariel Jerozolimski / Bloomberg

24. Leumi Bank Building (1969) In Tel-Aviv, Israel

Architect: Gershon Zippor

Photo: Stefano Perego

One thing I think is essential for people to understand about this style is that it’s challenging to execute well. For each element of the building that was designed, an accompanying wooden mold also had to be designed and built for pouring the concrete. The process involved creating two intricate sets of drawings, then making the molds before the building could be poured into place. Shipbuilders from Canada were even hired to build some of Le Corbusier’s most complex wooden forms for the Carpenter Center on Harvard’s campus.

Everything had to be meticulously planned far in advance. And, if you’re interested in seeing this done well, I encourage you to check out Marcel Breuer’s drawings, which are in the Syracuse University Archives. People who hate brutalist architecture might appreciate Breuer’s elegant U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Headquarters drawings. I genuinely believe that the architects who built these buildings were trying to make a positive mark on the landscape, and the eventual—sometimes immediate—backlash against these buildings caught them off guard.”

25. National Cooperative Development Corporation – NCDC Building (1978) In New Delhi, India

Architect: Kuldip Singh

Photo: Ariel Huber

26. Palazzetto dello Sport / Palace of Sport (1958) In Rome, Italy

Architect: Pier Luigi Nervi

27. Van Nuys Community Police Station (1964) In Los Angeles, California, U.S.

Architecture firm: Daniel Mann Johnson & Mendenhall

The future of brutalist architecture appears to be characterized by a mix of possibilities. While it experienced a period of polarized opinions and a decline in popularity during the late 20th century, there has been a resurgence of interest and appreciation for the style in recent years. Alex Anderson says this is partly because many buildings are now 50-70 years old. “They have become old enough to need repair and remodeling. Often this presents excellent difficulty; massive concrete structures are difficult and expensive to change. Is it more economical to fix them or tear them down? The intensity of feeling around brutalist Buildings makes this question incredibly challenging.

Aside from the economic and aesthetic issues, this has an essential environmental side. Environmentally, saving and remodeling older buildings is almost always better than tearing them down. This is especially true when their primary material is concrete, which sequesters a lot of carbon and takes a lot of energy to break it down. Over the following decades, this debate will recur for many brutalist Buildings that must be repaired or remodeled. I’m afraid public sentiment will turn against many of these buildings, and they will be torn down. Others will generate public opinion and find vocal champions to rally to support their preservation. I’m optimistic that many of the best examples of brutalist architecture will survive. It will help more people better understand brutalist Buildings and why they are worth preserving. I’m hoping this article contributes to this!”

28. Residential Complex (1976) In Tbilisi, Nutsubidze Str., Georgia

Architects: Otar Kalandarishvili and Guizo Potskhishvili

Photo: Roberto Conte

29. Istočna kapija (officially Rudo) – East Gate Residential Towers (1976) In Beograd / Belgrade, Serbia

Architect: Vera Ćirković

30. Holy Spirit Church (1976) In Stuttgart, Germany

Architect: Rainer L. Neusch

Angela Person agrees that brutalist Buildings garner increased attention because many have crossed the 50-year mark. “It’s time to begin making difficult decisions about updating these buildings to meet 21st-century standards—for example, replacing HVAC systems and glazing—or if they should be torn down, which is very expensive, especially when a building is entirely made of poured concrete.

This has led to high-profile historic preservation debates, ultimately garnering media (and social media) attention. For example, in a multi-year battle over the Third Church of Christ, Scientists in Washington, D.C., Its congregation sued D.C. to challenge its historic landmark status and ultimately won the right to tear it down. Similar conversations are being had about these aging buildings all over the world. In some cases, like the Barbican Centre in London, significant resources are invested in renewal efforts. Owners and occupants have tough decisions about whether brutalist Buildings can be reasonably adapted to serve another 50 years, especially given that the most sustainable building is often already built.”

Another reason people think brutalist buildings are experiencing a resurgence is that they are very photogenic. “On social media, we’re constantly being exposed to the beautiful imagery of their gray, sculptural forms contrasted against blue skies. Graphically, they come across very strongly in photos and contrast highly against most surroundings. Today, these buildings and their imagery pop up in image-centric places—on dedicated Instagram pages, beer cans, and video games. They might not always be fun to inhabit, but they’re fun to look at in photos. Something is striking and almost science fiction-like about how these buildings are present on film.”

31. Burroughs Welcome Company Headquarters, Later Elion-Hitchings Building (1972) In Research Triangle Park, Durham, North Carolina, US

One of the old favorites, among others, to Keith Stilwell.

Architect: Paul Rudolph

32. Pope St. John XXIII. Church (1969) In Cologne / Köln, Germany

Architect: Heinz Buchmann

33. Star Tower at Campus De Uithof, University of Utrecht (1964) In Utrecht, Netherlands

Architect: Sjoerd Wouda

Photo: Arjan den Boer

I call all brutalist-style enthusiasts or anyone intrigued by this captivating architectural style! Dr. Angela Person shared that she is working on an exhibition called Brutal DC, which will open at the South Utah Museum of Art (SUMA) in October, with plans to travel to a major venue in Washington, D.C., next year. “It explores the past, present, and future of selected brutalist architecture landmarks in D.C. I’m honored to partner with award-winning photographer Ty Cole, amazing architectural writer Deane Madsen, and the staff at SUMA to make it possible. I hope you’ll check it out!”

34. Visvesvaraya Complex, The Tower (Started In 1974, Completed In 1980) In Bangalore / Bengaluru, India

Architect: Charles Correa

35. Central Technical School Art Centre (1962) In Toronto, Canada

Architect: Macy DuBois

Photo: Vik Pahwa

36. All Saints Or Farkasréti Church (1977) In Budapest, Hungary

Architect: István Szabó

37. Rivergate Convention Centre (1968), Demolished In 1995 In New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.

Architectural firm: Curtis and Davis Architects and Planners

38. Newspaper “Tercüman” Office Building (1974) In Istanbul, Turkey

Architects: Günay Çilingiroğlu and Muhlis Tunca

39. Former Avon Factory And offices (1969) In Frenchs Forest (Near Sydney), Australia

Architectural firm: Brown Brewer & Gregory

40. Church / Église Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay (1966) In Nevers, France

Architects: Claude Parent and Paul Virilio with Odette Ducarre, Morice Lipsi, and Michel Carrade

Photo: Aglaia Konrad

41. Former School (1967), For Sale In Idaho Springs, Colorado, US

Architect: not published

42. Ferantov Garden Residential Complex (1973 Or 1975) In Ljubljana, Slovenia

Architect: Edvard Ravnikar

Photo: Philipp Heer

43. BKK Budapest Transport Center (1978) In Budapest, Hungary

Architect: not published

Photo: László Róka

44. Administrative Center of Bahia (1973) In Salvador de Bahia, Brazil

Architect: João Filgueiras Lima

Photo: Kaki Afonso

45. Building Girón (1967) In Havana, Cuba

Architects: Leonardo Finotti, Antonio Quintana Simonetti and Alberto Rodríguez Surribas

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to our top stories.

Discussion about this post